Real-Time Mask Detection

Multithreaded C++ application

Abstract

I built a multithreaded C++ application using OpenCV’s Deep Neural Network API. The approach achieves demonstrably robust, real-time object detection with input image, video, and device (e.g. webcam) streams. In this page, I will discuss the end-to-end implementation; from dataset and training, to inference and application design.

Introduction

Over this past year, I’ve been working through the second offering from OpenCV’s AI courses. There were three projects for this course; the first two I’ve already written up here and here. For the third project, I decided to work through it differently than the rubric prescribed. Rather than just putting together a simplified submission to satisfy project requirements, I wanted to do something practical that could be used as a baseline for future computer vision projects, both personal and professional. In this writeup, I will discuss the solution that created the gif above with particular emphasis on the following aspects:

- Problem Statement

- Compositional Elements (i.e. Tools Used)

- Dataset

- Model Selection and Training

- Application Design and Implementation

Project Details

I have posted the project code on GitHub. The README covers steps for reproducing results, but I will go over high-level aspects of the project in the subsequent sections of this writeup to give more context.

Problem Statement

Given image data input from one of the following sources:

- Image file

- Video file

- Streaming device (e.g. webcam)

perform inference on the data to detect faces and determine whether or not they are wearing face coverings (i.e. masks).

The problem is broken into two pieces:

- Training - supervised training process to “learn” the desired detector

- Testing - deploy the trained model to perform inference on new input

Solution Objectives

In this project, I aim to solve the problem stated above with a solution that is:

- trained using freely available annotated image data - this is a consideration for training alone

- real-time - Input frames-per-second (FPS) = Output FPS, a consideration for testing

- configurable at runtime - The user has multiple options available for experimentation without recompiling the application; this is considered for testing alone

- built entirely using open-source components - this is a joint consideration for both stages of the project

Tools

The open-source software frameworks used in the project are:

- C++(14) standard library - the core C++ API, including

std::threadand, relatedly,std::mutex - OpenCV - for image processing, visualization, and inference utilities

- DarkNet - for model selection and training

- Docker - for deploying containers with all compile- and build-time dependencies satisfied

Dataset

The dataset has been prepared with the prerequisite YOLO format already satisfied. For other available datasets, consider looking on Kaggle.

The dataset needed some cleanup and minor post-processing to be usable in training; see the project README for specifics (incl. instructions).

Model Selection and Training

YOLO is a popular one-stage object detector that jointly estimates bounding boxes and labels for objects in images. It comes in several variants and versions, with YOLOv4 being one of the most recent. For model selection, I considered mostly inference time, which is inversely proportional to inference_rate in FPS, mean average precision (mAP), difficulty to train, and difficulty in deploying in a command-line app with OpenCV. This last consideration was most important for this project. Ultimately, I wanted to use OpenCV’s utilities for image acquisition and post-processing. This desire arose from the high-level of maturity of both the source code and the online documentation (including tutorials).

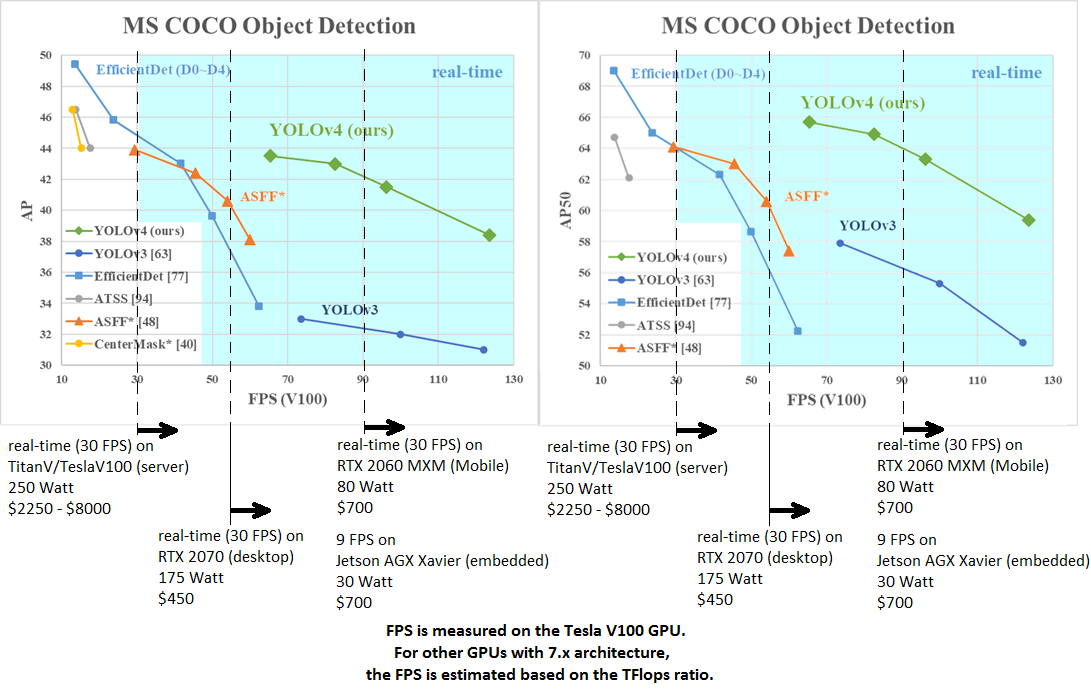

YOLOv4 combines inference speed with accuracy

The following chart from the YOLOv4 paper shows favorable model performance on the standard COCO when compared to competing methods:

When referring to the chart above, the top-right of the chart is where I want to focus on: better models for the problem at-hand will show data points in this region since these are the fastest and most accurate. As you can see in the chart, YOLOv4 achieves results comparable (within ~5% average precision) with the most accurate models considered, while significantly outperforming those same models in terms of inference speed.

YOLO model variants have a peculiar constraint on input image size for training and inference: the image height and width, in pixels, needs to be a multiple of 32. This is because of the binning of image regions used to perform object detection without generating a priori region proposals (as in two-stage methods like Fast-RCNN). The larger the input image size, typically, the higher the mAP score. This increased accuracy comes with a hit to inference speed. For this project, I trained two different configurations - one with (h, w) = (256, 256), the other with (h, w) = (416, 416). I stopped here because, for me, the project wasn’t about maximizing accuracy so much as putting together the real-time application using the trained model. In practice, I found the accuracy, time-to-train, and inference time acceptable for this project with (h, w) = (416, 416). I will discuss this further in the conclusion.

Training

YOLOv4 is easily, and efficiently, trained using Darknet. Darknet is a C/C++ framework for neural network model optimization written to train the original YOLO. The author of the original YOLO paper no longer maintains the Darknet, however one of the authors of the YOLOv4 paper has created, and maintains, an updated fork. The repo has instructions to easily train YOLOv4 (or v3, for that matter) for custom object detection problems; i.e. those that seek to detect objects not in the COCO dataset. I followed these same instructions to train the mask detection model used for inference.

Download pre-trained task-specific weights

If you want to avoid having to retrain the model, here are links to pre-trained model weight files:

Application Design and Implementation

For this part of the project, the major aspects considered were:

- Multithreading and Data Management - How is data acquired, processed, and shared safely?

- UI/UX - How will users run and interact with the application?

- Measuring Performance - How is runtime performance of the application assessed?

Multithreading and Data Management

There are naturally concurrent ways of viewing this problem; data will be generated from the input source independently of subsequent processing. This means we can easily separate input capture from other processing in its own separate thread. The perceived main bottleneck in the application will be the forward pass of YOLOv4 for inference, so I wanted to avoid blocking any other step in the execution pipeline. To accomplish this, I used a second thread that does preprocessing of an input image and then performs inference using the trained YOLOv4 model. After performing inference, the bounding boxes and labels are drawn onto the original raw image frame in the third thread.

The big assumption underlying the design of the application was that YOLOv4 would be the computational bottleneck, therefore it should be isolated from all other steps in the computational loop to prevent blocking data acquisition and post processing steps. In practice, with my system configuration, the bottleneck was not nearly as large as I expected. I’ll discuss this more in the conclusion.

The core application engine is an asynchronous sequential pipe composed of multiple processing thread: each processing thread has input and output queues that are read from / written to when new data is available. The main thread does initialization, handles user input - both at launch via CLI options, as well as trackbar moves on the output GUI, and plots the GUI output with data generated by the processing threads. Concurrent accesses are managed using a locking mechanism - a mutex - at the data structure level; each data structure has its own mutex to ensure data integrity.

In summary, there are four threads employed in the solution:

- Thread 1 (main thread) - initialization, user I/O, and performance metric capture

- Thread 2 (raw input capture) - read from input stream

- Thread 3 (inference) - preprocess and YOLOv4 forward pass

- Thread 4 (post-processing) - draw bounding boxes, with labels, and apply confidence and non-max suppression thresholding

UI/UX

There are two main components considered: a command-line interface (CLI) and an interactive GUI. The core design principle for the application UI/UX is runtime configurability; a user should be able to choose from several available options when launching the application. This functionality enables rapid experimentation without the necessity of slow and tedious recompilation.

CLI

The command-line interface uses OpenCV’s CommandLineParser to expose the following configurable options:

//! command-line inputs for OpenCV's parser

std::string keys =

"{ help h | | Print help message. }"

"{ device | 0 | camera device number. }"

"{ input i | | Path to input image or video file. Skip this argument to capture frames from a camera. }"

"{ output o | "" | Path to output video file. }"

"{ config | | yolo model configuration file. }"

"{ weights | | yolo model weights. }"

"{ classes | | path to a text file with names of classes to label detected objects. }"

"{ backend | 5 | Choose one of the following available backends: "

"0: DNN_BACKEND_DEFAULT, "

"1: DNN_BACKEND_HALIDE, "

"2: DNN_BACKEND_INFERENCE_ENGINE, "

"3: DNN_BACKEND_OPENCV, "

"4: DNN_BACKEND_VKCOM, "

"5: DNN_BACKEND_CUDA }"

"{ target | 6 | Choose one of the following target computation devices: "

"0: DNN_TARGET_CPU, "

"1: DNN_TARGET_OPENCL, "

"2: DNN_TARGET_OPENCL_FP16, "

"3: DNN_TARGET_MYRIAD, "

"4: DNN_TARGET_VULKAN, "

"5: DNN_TARGET_FPGA, "

"6: DNN_TARGET_CUDA, "

"7: DNN_TARGET_CUDA_FP16 }";

Input source, either from file or streaming device, is automatically verified and if it is not compatible with certain assumptions about file extension or is otherwise unable to be opened (e.g. the filename doesn’t exist), the application cleanly exits and notifies the user with a clear description of the error.

The inputs backend and target are used to define the computational model for forward inference on neural network models with OpenCV’s Deep Neural Network API. The options available are dependent upon the hardware (and software) resources available, as well as the compile flags used, when compiling OpenCV. I took this shortcoming into account in the UX design; if the user requests a (backend, target) pairing that is unavailable, the application will cleanly exit with a notification to the user. The ability to change the computational resources used at runtime, including hardware, is hugely valuable for experimentation.

Users can also try out different trained models quickly and reliably by using different config and weights options.

Throughout all options, care was taken to ensure that corner-cases encountered trigger clean exits with descriptive error messages. This way, the user knows where they went wrong and how to address the problem encountered.

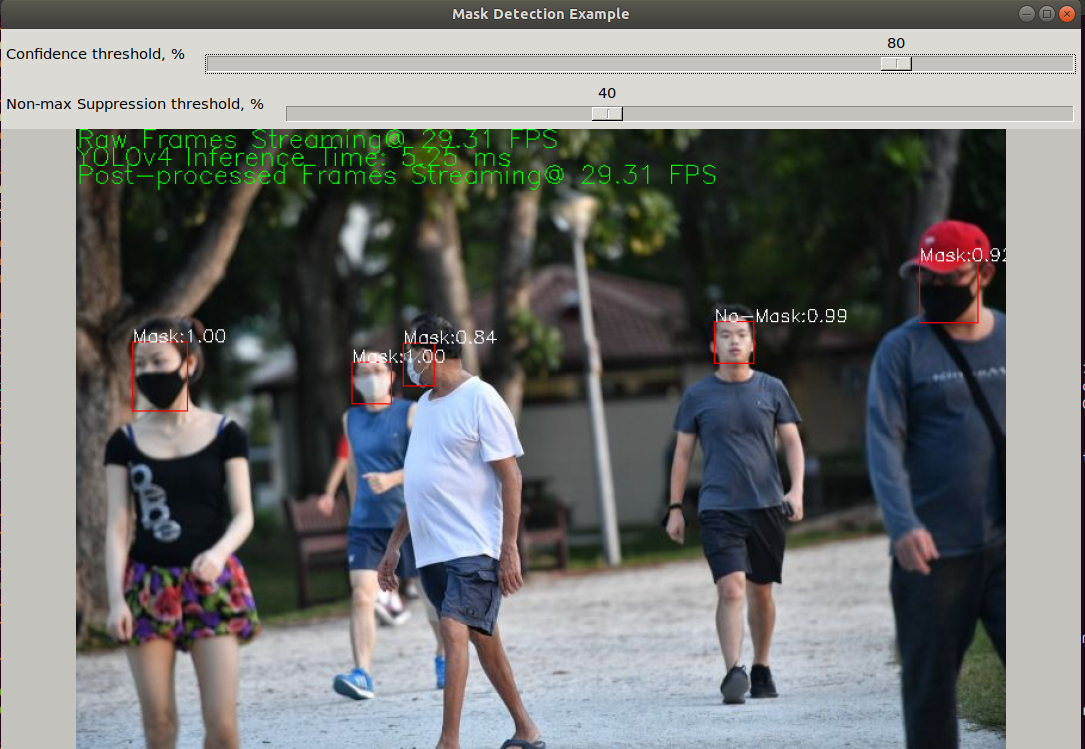

GUI

The final GUI is shown above. The GUI has two trackbars - one for confidence thresholding, the second for non-maximum suppression thresholding. Each trackbar is tied to an action that updates the runtime threshold for confidence and non-max suppression, respectively. By modifying these values during application execution, the user can experiment in real-time and identify prediction sensitivities to these parameters.

Displayed in the final image output are performance metrics (which will be discussed later), as well as detected bounding boxes with classification and confidence threshold displayed for each detection.

Final remarks about UI

Recall that there are three input types available:

- Image file

- Video file

- Streaming device (e.g. webcam)

Input types 1 and 3 will stream indefinitely; by design for type 1 and naturally for type 3. Video files, by contrast, have a natural exit point when the input stream is exhausted (i.e. when the video ends). To handle input from all three types seamlessly, the user can trigger exit at any time by typing the Esc key. For video files, the application will exit cleanly either when the video file ends or, if the video file is still open and streaming, by typing the Esc key.

Measuring Performance

In the top-left of the GUI shown here, there are three performance parameters shown:

- Raw frame rate - input capture rate measured in FPS

- Model inference time - time to perform forward pass of YOLOv4 measured in milliseconds

- Postprocessing frame rate - processing rate of final output frames measured in FPS

These metrics give the user a way of quantifying application performance, including real-time factor. Real-time factor is measured as (input frame rate) / (output frame rate). A real-time factor of “1” means the application can be classified as “real-time”, since (input rate) = (output rate).

Concluding Remarks

Throughout this writeup, I’ve presented my candidate design for a real-time mask detector built using C++, OpenCV, and YOLOv4. Some of the key takeaways of this project were:

- YOLOv4 is really fast. On my older GPU, I was still able to get inference at ~200FPS. This was really surprising given the YOLOv4 results on COCO presented in the YOLOv4 paper. I went into this project thinking that I needed multithreading to achieve a real-time factor >~50%, but I was way wrong about this in my initial assessment. Caveat: in initial investigations using the CPU backend, streaming dropped to ~3FPS, which would have a real-time factor ~0.1 for a 30FPS streaming device.

- OpenCV presents a nearly end-to-end API for C++. With its ability to perform timing analyses, parse command line arguments, load and process images, …, OpenCV provides a ton of capability for computer vision practitioners.

- Darknet is really nice as a training API for YOLO-based object detectors. The API is simple to use and fast when compiled with NVIDIA’s cuDNN library.

If I were to continue work on this project, I would investigate the following:

- Training and deploying models with larger height and width of input. Because the the frame rate was so high when using my GPU for inference, I think that I could use the larger input size to get a more accurate detector that is still real-time.

- Deploying to embedded devices. Because of the portability of my solution, enabled by Docker, I believe that I could deploy the solution to an NVIDIA edge device, like a Jetson Xavier NX with relative ease.

I had a lot of fun working on this project. OpenCV continues to build upon past successes to create new value for its myriad end-users (myself included). The Deep Neural Network module is surprisingly easy to use, is well-documented, and has many available tutorials online.

Some Additional References

- Object Detection Example from OpenCV

- YOLO example from LearnOpenCV

- Object Detection for Dummies - Part 1 of 4-part series